{Photos by rocketlass.}

From "Bookshop Memories," by George Orwell, originally published in the Fortnightly, November 1936

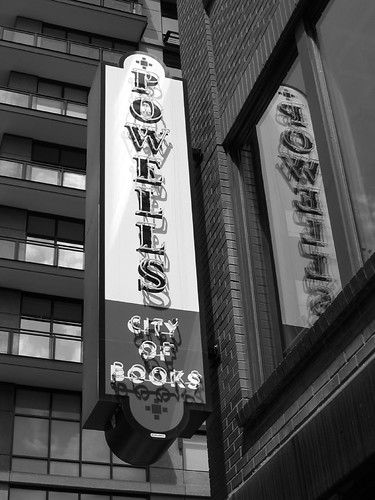

Given a good pitch and the right amount of capital, any educated person ought to be able to make a small secure living out of a bookshop. . . . Also it is a humane trade which is not capable of being vulgarized beyond a certain point. The combines can never squeeze the small independent bookseller out of existence as they have squeezed the grocer and the milkman.Good to see that even the best prognosticators can be wrong sometimes--though it's somewhat depressing to realize that in this case Orwell was wrong because he shed his habitual pessimism about society's ability to dehumanize any activity. Actually, I suppose we can at worst give Orwell half-marks for this prediction: having in my time worked in a small, serious independent bookshop (as well as in a small London chain), I agree with the sense of his first statement, that an independent bookstore is still a viable proposition for a smart (and, as he later notes, hard-working) entrepreneur. And the combines--which do some things extremely well, it must be said--have certainly not wiped out the independents; though their ranks are considerably thinned, there are still good independents in most good-sized American cities, while those of us who work in Hyde Park in Chicago are particularly spoiled by the riches of the Seminary Co-op stores.

"Bookshop Memories," which I encountered in Books v. Cigarettes (2008), a new volume in Penguin's beautifully conceived and designed Great Ideas series, also offers some skewering of the typical bookstore customer that will still resonate with booksellers today. Take this, which would fit comfortably with the retail horror stories found at the Book Lady's Blog:

Many of the people who came to us were of the kind who would be a nuisance anywhere but have special opportunities in a bookshop. For example, the dear old lady who "wants a book for an invalid" (a very common demand, that,), and the other dear old lady who read such a nice book in 1897 and wonders whether you can find her a copy. Unfortunately she doesn't remember the title or the author's name or what the book was about, but she does remember that it had a red cover. . . . In a town like London there are always plenty of not quite certifiable lunatics walking the streets, and they tend to gravitate towards bookshops, because a bookshop is one of the few places where you can hang around for a long time without spending any money.None of this would have come as a surprise to a reader who had already encountered Orwell's first novel, Keep the Aspidistra Flying, which had been published about seven months earlier. Its opening chapter paints about as unromantic a picture of bookselling--and, it must be said, of humanity--as is possible. On the second page we get this:

This was the lonely after-dinner hour, when few or no customers were to be expected. He was alone with seven thousand books. The small dark room, smelling of dust and decayed paper, that gave on the office, was filled to the brim with books, mostly aged and unsaleable. On the top shelves near the ceiling the quarto volumes of extinct encyclopedias slumbered on their sides in piles like the tiered coffins in common graves.Later, two of the customers of the shop's lending library enter:

"Good afternoon, Mrs Weaver. Good afternoon, Mrs Penn. What terrible weather!"Little does Mrs. Penn know that Gordon holds her love of Galsworthy in as low esteem as Mrs. Weaver's preference for Ethel M. Dell. In fact, Orwell soon shows us ably fielding a request from the other end of the spectrum:

"Shocking!" said Mrs Penn.

He stood aside to let them pass. Mrs Weaver upset her rush basket and spilled on to the floor a much-thumbed copy of Ethel M. Dell's Silver Wedding. Mrs Penn's bright bird-eye lighted upon it. Behind Mrs Weaver's back she smiled up to Gordon, archly, as highbrow to highbrow. Dell! The lowness of it! The books these lower classes read! Understandingly, he smiled back. They passed into the library, highbrow to highbrow smiling.

Mrs Penn laid The Forsyte Saga on the table and turned her sparrow-bosom upon Gordon. She was always very affable to Gordon. She addressed him as Mister Comstock, shopwalker though he was, and held literary conversations with him. There was the free-masonry of highbrows between them.

"Oh no, not her. She's too Deep. I can't bear Deep books. But I want something--well, you know--modern. Sex-problems and divorce and all that. You know."Gordon, we realize, has succumbed to that toxic mix of contempt and general misanthropy (always accompanied by a dash of the bitters of self-loathing) that perpetually tempts every retail drudge. It reaches its dizzying, soul-staining height in this exchange, which Orwell surely wrote from repeated personal experience:

"Modern, but not Deep," said Gordon, as lowbrow to lowbrow.

A couple of old creatures, a tramp or a beggar and his wife, in long greasy overcoats that reached almost to the ground, were shuffling towards the shop. Book-pinchers, by the look of them. Better keep an eye on the boxes outside. The old man halted on the kerb a few yards away while his wife came to the door. She pushed it open and looked up at Gordon, between grey strings of hair, with a sort of hopeful malevolence.Could there be a phrase more apt than "a sort of hopeful malevolence?" Nearly ten years after I left bookselling, there are days when I still miss it; a quick flip through Keep the Aspidistra Flying is usually enough to cure it. Forevermore, a browser and a buyer I'll be.

"Ju buy books?" she demanded hoarsely.

"Sometimes. It depends what books they are."

"I gossome LOVELY books 'ere."

She came in, shutting the door with a clang. The Nancy glanced over his shoulder distastefully and moved a step or two away, into the corner. The old woman had produced a greasy little sack from under her overcoat. She moved confidentially nearer to Gordon. She smelt of very, very old breadcrusts.

"Will you 'ave 'em?" she said, clasping the neck of the sack. "Only 'alf a crown the lot."

"What are they? Let me see them, please."

"LOVELY books, they are," she breathed, bending over to open the sack and emitting a sudden very powerful whiff of breadcrusts.

''Ere!" she said, and thrust an armful of filthy-looking books almost into Gordon's face.

They were an 1884 edition of Charlotte M. Yonge's novels, and had the appearance of having been slept on for many years. Gordon stepped back, suddenly revolted.

'We can't possibly buy those," he said shortly.

"Can't buy 'em? WHY can't yer buy 'em?"

"Because they're no use to us. We can't sell that kind of thing."

"Wotcher make me take 'em out o' me bag for, then?" demanded the old woman ferociously.

No comments:

Post a Comment