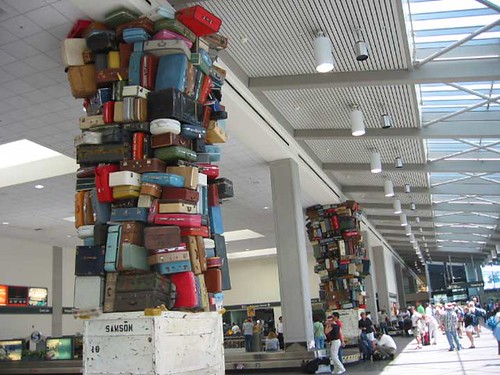

[Photo by

rocketlass]

Because it seems I've been doing more than my share of traveling lately, I offer up some notes on getting around.

From

Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War for Independence (2007), by John Ferling:

Little time passed before it was evident that the leadership had grossly underestimated the difficulties that would be confronted in the wilds of Maine. Within the initial three days--over a fifty-mile stretch that drew the army well beyond Maine's last settlement--the soldiery came on a succession of churning rapids and disquieting falls, including some "very bad rips," as one soldier noted, which resulted in far more portaging than had been anticipated. . . . The men were wet constantly--"you would have taken" them for "amphibious Animals," [Benedict] Arnold wrote to Washington--and the night temperatures routinely plummeted below freezing. Each morning the men awakened, said one, to find their clothing "frozen a pane of glass thick." Before he had been in the interior of Maine a week, Arnold reported the "great Fatigue" of his men and quietly worried over whether he had brought along a sufficient supply of food and blankets. The men grew concerned as well, not only about the dwindling supplies. They "most dreaded" the cold, fearing not only disease, but anxious at their fate should they fall on ice and fracture a leg or hip while deep in the wilderness.

Well, maybe it's better if one keeps out of the wilderness (let alone the Continental army), sticking to cities instead?

From

Hubbub: Filth, Noise, and Stench in England (2007), by Emily Cockayne:

In a few cases [of deadly road accident] the driver was found guilty of causing an accident by failing to pay due care and attention. The attitudes of the carters and coachmen were questioned. In particular, commentators complained about the lackadaisical way the drivers positioned themselves on their vehicles so that they could not easily see the road ahead. It was recorded in 1692 that "most of the carters, Carmen, and draymen that pass and repass with their several carts, carriages, and drays through the public streets, lanes and places [of London and Middlesex] . . . make it their common and usual practice to ride negligently on their several carts." Often nobody guided the horse, "so that oftentimes their horses, carts, carriages, and drays run over young children and other their Majesties' subjects, passing in the streets about their lawful occasions, whereby many lose their lives."

It seems that at least one recognizable type of driver-for-hire has persisted through the centuries; imagine how much more imperiled the lives of those seventeenth-century Londoners would have been had their draymen had cellphones on which to chatter away throughout their shifts.

Speaking of which, Stacey saw a cabbie yesterday who would, I think, have done well in the rough-and-tumble of seventeenth-century London: after his running of a red light led to his cab blocking an intersection, he was verbally assailed by a stuck motorist--which he took as an occasion to, after shouting to his far, "Hold on!", get out of his cab and go fight the other motorist. The last Stacey saw of the incident was some police cars heading that way, lights flashing.

So maybe a train would be a better idea?

From a letter from

E. B. White to Henry Allen of 22 February, 1955 telling about White's attempt to catch a 6:30 train,collected in

Letters of E. B. White (1977, 2006):

I looked at my watch again and it said 6:31. We screamed into the station yard, jumped out, and the engineer saw us coming and I guess he took pity on me. They had the train all locked up, ready to go, the bell was ringing for the start. The taxi driver grabbed my bags and whirled down the platform, and I trotted behind , carrying my fish pole and the Freethy lunch box. The trainman saw this strange apparition appearing, and he opened up the coach door. I plunged on board and the driver threw the bags on, and away we went. I had no ticket, no Pullman receipt for my room, just a fish pole. For the next hour or two, I was known all through the train as "that man." But the porter got interested in my case, the way porters do, and he stuck me in the only empty bedroom and told me to sit there till we got to Waterville. The conductor stopped by, every few minutes, to needle me, and between visits I would close the door and eat a sandwich and mix myself a whiskey-and-milk, in an attempt to recuperate from my ordeal. At Waterville, the conductor charged in and said: "Put on your hat and follow me!" Then he dashed away, with me after him. He jumped off the train and disappeared into the darkness. When I located him in the waiting room he looked sternly at me and said, "Are you the man?"

"I'm the man," I replied.

"Well," he said, "go back and sit in the room."

Then planes, and luxury travel--being met at the airport and whisked away to a spa and all that instead.

From a letter from

Jessica Mitford to Robert Truehaft of November 15, 1965, collected in

Decca: The Letters of Jessica Mitford (2006):

I arrived more dead than alive, the plane being 2 hours late in the end. Shall draw a veil over that. Was met by a gliding lady (they all glide here, rather than walk) and driver. The latter drove me here, the glider having to leave and fetch another arriving flower. As you can imagine, I was pretty well sloshed by the time the plane finally downed.

Ultimately, perhaps the key is not to care about the mode, but just to set oneself into motion and hope for the best. I'll leave that for

James Laughlin, who in the following note from his sort-of-autobiography,

The Way It Wasn't (2006), seems not much to care about the details of his upcoming trip--and while I suppose such blithe unconcern is easier for a wealthy heir than for the rest of us, his approach does seem likely to be satisfying.

I am going to see Gertrude Stein for a few days on Friday and then I am going to Lausanne -- Basel -- Freiburg -- Strassbourg -- Stutgart (H. Baines) -- Wurzburg -- Erfurt -- Leipzig -- Dresden -- Prague -- Brunn -- Bratislava -- Budapest -- Vienna -- Linz -- Salzburg -- Ljubljana -- Zagreb -- Dubrovnik. What all this will add up to is not known, but if I write a poem in each place, I shall have had some practice in this matter.

Or I suppose you could travel by not traveling at all, as seems one explanation of an image featured in a show that

Luc Sante's currently curating at apexart,

The Museum of Crime and the Museum of God. It's an old black-and-white print that incorporates two photos, the larger one showing a black man in clerical robes waist-deep in a wide, muddy stream, an "x" scratched into the print near him.. The caption, apparently typed on it at the time the photo was printed, reads:

Reverend C. H. Parrish, D.O., standing in the River Jordan, April 13, '04, a short distance from the place where John the Baptist baptized the Saviour. See cross-mark.

The inset photo shows the same man in the same robes standing under a tall, thick, knobbly tree, and the caption reads:

Dr. Parrish standing under the Oldest Olive Tree (1800 years old) in the Garden of Gethsemane, April 16, '04.

Meanwhile, the print itself is captioned thus:

Photographed while attending the World's Fourth Sunday-School Convention, held at Jerusalem, April 18, '04.

All of which would be fine except that the two photos are obvious fakes: the man, who is exactly the same in both photos, has been cut from a different photo and pasted in place. In the river photo, he's been cut in half to show that he's partially submerged, while the olive tree photo presents him whole.

Now, perhaps there's a reason for this fakery. Perhaps the Reverend Parrish's photos from the Sunday-School conference simply didn't turn out, and he felt that a little cut-and-paste work would be more likely to draw his parishioners closer to holiness than seeing nothing at all from his trip. But what if that's not the case?

What if the Reverend Parrish didn't go to Jerusalem at all? Presuming that his parishioners paid for his trip, just what, this hundred years on, do we think he actually did with the money? Did it go to a lady friend in dire need of mink? Was it laid on a can't-miss horse? Or did it support a trip to some lesser locale than Jerusalem--someplace far less exotic, historical, and sacred, but for all that far more congenial, hospitable, and fun? Someplace like Atlantic City?

Oh, that's probably enough speculation for a lovely summer Saturday. I'll let

Sammy Cahn close it out, with the end of his "It's Nice to Go Trav'ling":

It's very nice to be footloose

With just a toothbrush and comb

It's oh so nice to be footloose

But your heart starts singin' when you're homeward wingin' across the foam.

It's very nice to go trav'ling

But it's oh so nice to come home.

As

Frank himself might say, ain't that the truth.