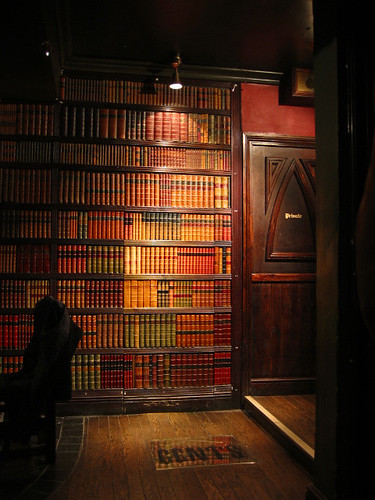

When, presently, Philippa set wide the great double doors of the library, the curator was not in the chamber. The night sky, indigo through the thirteen dormer windows, looked down upon the tiered ranks of fretted shelves, twelve on each side, which held the nine hundred manuscripts lovingly collected by Charles, and the five hundred Greek works left by King Henri's father, along with the others brought him from abroad by his collectors, and looked after him by Bude. Go tell my wife, that curator had said without looking up from his book, when fire broke out and raged through his lodgings. Go tell my wife. I do not concern myself with domestic matters.

It's not the absorption that heartened me, but the numbers: that was the royal library of the King of France in 1557, and it had fewer volumes by far than my own. I am endlessly fortunate, and that reminder leavens the sense--always bubbling up after a week of little reading--that I'm falling behind, failing to get to books I've brought home and very much want to dive into. The surfeit is itself a blessing, and one best met by gratitude and patience.

That thought sent me to Borges's essay on blindness from Seven Nights. He writes of his appointment as director of the Argentine National Library,

I received the nomination at the end of 1955. I was in charge of, I was told, a million books. Later I found out it was nine hundred thousand--a number that's more than enough. (And perhaps nine hundred thousand seems more like a million.)Borges's philosophical take is helpful. More restorative, perhaps, was a rainy autumn Sunday of sipping cider, sitting by the fire, and reading for hours. It's reminded me that no sensible reader is on a quest for completeness; this is an endless task. In The Library at Night, Alberto Manguel describes it well:

Little by little I cam to realize the the strange irony of events. I had always imagined Paradise as a kind of library. Others think of a garden or of a palace. There I was, the center, in a way, of nine hundred thousand books in various languages, but I found I could barely make out the title pages and the spines. . . . I remembered a sentence from Rudolf Steiner, in his books on anthroposophy, which was the name he gave to his theosophy. He said that when something ends, we must think that something begins. His advice is salutory, but the execution is difficult, for we only know what we have lost, not what we will gain. We have a very precise image--an image at times shameless--of what we have lost, but we are ignorant of what may follow or replace it.

{M]ore than anything else, the LIbrary of Alexandria was a place of memory, of necessarily imperfect memory. . . . Honouring Alexandria's remote purpose, all subsequent libraries, however ambitious, have acknowledged this piecemeal pnemonic function. The existence of any library, even mine, allows readers a sense of what their craft is truly about, a craft that struggles against the stringencies of time by bringing fragments of the past into their present. It grants them a glimpse, however secret or distant, into the minds of other human beings, and allows them a certain knowledge of their own condition through the stories stored here for their perusal. Above all, it tells readers that their craft consists of the power to remember, actively, through the prompt of the page, selected moments of the human experience.The task is endless, and so are the satisfactions.