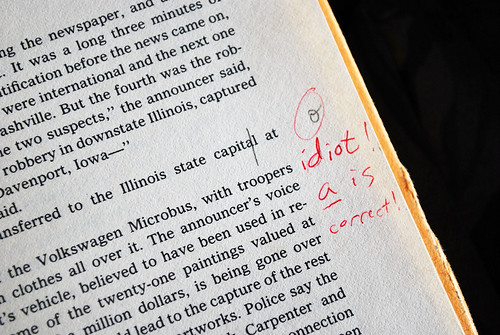

{Photo of an erroneous erratum in the Regenstein Library's copy of Richard Stark's Plunder Squad by rocketlass.}

In my recent reading I've happened across three little bits about publishing that seemed worth sharing. First, from Vere H. Collins's Talks with Thomas Hardy at Max Gate (1928), a discussion between the author and Hardy about publishing errata:

H: There are a considerable number of misprints in the Collected Edition [of his poems]. Macmillan has issued an errata slip. Had your copy one?I'm disapointed that "hairy does" didn't become "hairy toes" instead; we could have had hobbits decades earlier!

C: No, but I bought the book when it first came out.

H: I will get a copy of the slip for you. [He leaves the room and returns with an errata slip.] That will save you from having to buy a revised edition. I cannot understand how mistakes occur in a printed book when a proof has been corrected properly.

C: Sometimes a word or line drops out when the formes are being moved and the printer resets carelessly without referring to the proof.

H: I remember Tennyson being very much annoyed because one of his poems was printed with "hairy does" instead of "aery does." On another occasion "mad phrases" became "mud phrases."

Then there's this scene from P. G. Wodehouse's Uncle Dynamite (1948), wherein a woman recounts how her brother, a small publisher, found himself in trouble after printing taking on a job for a wealthy--and stodgy--old man:

"[H]e said one thing that gripped my attention, and that was that he had written his Reminiscences and had decided after some thought to pay for their publication. He spoke like a man who had had disappointments. So I said to myself, 'Ha! A job for Otis.'"If we were were playing "one of these things is not like the others," this last item would stand out like an unindicted tenant in the Illinois governor's mansion, but since I already had the first two passages on the brain it seemed worth appending when I came across it this afternoon. From Ross Macdonald's The Underground Man (1971), a glimpse of a way of looking at the life of a city that's nearly disappeared:

"I begin to see. Otis took it on and made a mess of it?"

"Yes. In a negligent moment he slipped in some plates which should have appeared in a book on Modern Art which he was doing. Sir Aylmer didn't like any of them much, but the one he disliked particularly was the nude female with 'Myself in the Early Twenties' under it."

I walked past the closed door of the Wallers' apartment and down the street to the nearest newsstand, where I bought the weekend edition of the Los Angeles Times. I lugged it home and spent most of the morning reading it. All of it, including the classified ads, which sometimes tell you more about Los Angeles than the news.The Times is still with us, but the classifieds are just about gone; would Craigslist offer Archer the same insight into the hope and desperation of his city?