Philip Hoare's The Sea Inside: Hoare's book is ostensibly about the sea, the creatures found there, and our relationship to them. But it's as much about Hoare's mind, and the places its questing takes him, as it is about those subjects. So we learn about St. Mark the Wrestler, who "cured a hyena whelp by spitting on his fingers and signing on its eyes." And about the bad rap that ravens get. And about Hoare's ice-cold ocean swims, and his quiet home, and his memories of family. And of course about whales. It's a meandering, byways and backroads book, and it's mesmerizing.

Lucy Lethbridge's Servants: A Downstairs History of Britain from the Nineteenth Century to Modern Times: A richly anecdotal history of servants in twentieth-century Britain. What more do you need to know? Seriously: it's hard to imagine any fan of twentieth-century British literature who wouldn't enjoy this, if for no other reason than to help them understand the mostly unspoken background to the fiction of the period.

Lee Sandlin's The Distancers: An American Memoir: Lee Sandlin's memoir of a number of his ancestors (great-aunts and uncles, mostly) achieves something admirable: it brings ordinary people from generations before ours to life, locates them in their place and time, and, without setting ourselves or our own times up as better, or more advanced, shows us just how different they were, how truly far away from the familiar you get as you walk back through the decades. At the same time, he tells a moving story of ordinary people (if strange, and even in some cases damaged--driven, as Anthony Powell put it, by their own furies) living quiet lives, destined to disappear from memory were it not that they had a descendant who became a writer, one who cares about what we lose when memories fade.

Terry Teachout's Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington: In a lean year for me for biographies, Duke was a treat. I already knew that Ellington was famously elusive and hard to get to know; what I didn't know is that not that much happened in his life: he formed the band, and while there were ups and downs afterwards, that was basically it. In a certain sense the band was his life. Despite that Teachout manages to keep the narrative compelling, primarily by reliably bringing it back to the music and the players. Maybe no one really knew Ellington, but by the end of Duke we understand his genius, and admire his contribution to our culture all the more.

Carl Watkins's The Undiscovered Country: Journeys among the Dead: A perfect accompaniment to autumn's annual serving of ghost stories, Watkins's book is packed with details of how the English related to their dead--restful and walkabout alike--in past centuries. From it I learned more about the ghost-story-hunting monk of Byland Abbey, discovered that the dead buried beneath the flagstones of churches did indeed sometimes disrupt services with an olfactory reminder of the whole dust to dust bit, and of a nineteenth-century druid who was an early advocate of cremation. I've learned to trust the Bodley Head's sense of a good history--they're always rich in quotation, anecdote, surprises, and analysis--and this is the best of the year of the type.

I've Been Reading Lately is what it sounds like. I spend most of my free time reading, and here's where I write about what I've read.

Showing posts with label Terry Teachout. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Terry Teachout. Show all posts

Wednesday, December 18, 2013

Wednesday, December 02, 2009

Props for Pops

I just finished reading Terry Teachout's wonderful new biography of Louis Armstrong, Pops, which is as good as its many rave reviews have said. Since everyone from the Times on down has weighed in with praise already, I'll just heartily second them, and share two things:

1 Throughout the book, Teachout keeps the music front and center, never letting us forget that that was what was most important to Armstrong himself. He frequently offers detailed analysis of songs, some of which were unfamiliar--but every time he described an unfamiliar song, I was able to go to Lala.com and listen to it. Lala is an online service that sells digital music--and, more important in this case, they also let you listen to any song in their library one time for free. This is the first music bio I've read since the site's debut, and having a legitimate, nearly unlimited source of reference tracks when reading a book like this makes the experience incalculably richer. If you're going to read Pops and you don't know Armstrong's music like the back of your hand already, do yourself a favor and have Lala at hand in your browser; you'll be glad you did.

2 One passage that really stuck with me was Teachout's account of the postwar demise of the big bands. I knew, as a casual fan of jazz, big bands, and popular song, that their disappearance was quick, but I had no idea it was this rapid:

The bottom fell out of big-band jazz in the winter of 1946. Time ran an obituary for the era: "The big brassy jazz bands had become a luxury that people were unwilling to pay for. . . . In the past eight weeks, Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Harry James, Les Brown and Jack Teagarden decided to disband. Gene Krupa and Jimmy Dorsey cut salaries. This week Woody Herman gave up too." [Armstrong's manager] Joe Glaser needed no journalist to read him the writing on the wall. "Promoters all over are going broke--bookings are being canceled at the last minute--I can name at least half a dozen Colored bands that will disband in the next 30 days and at least 30 white bands that will disband," he had written to Joe Garland that summer.Good god, that's dizzying. I suppose it's just another reminder--as people in the old live radio industry or the newspaper industry can attest--when tastes change and costs rise, things can fall apart really fast.

Because the holidays are nearing and cheer is the order of the day, I'm going to temporary refuse to apply that lesson to publishing. For now, after all, publishing still lives, books are still with us, and Pops is a beautiful example of the bookmaker's, no less than the biographer's art; may Armstrong's smile grace many a stocking this Christmas.

Friday, June 19, 2009

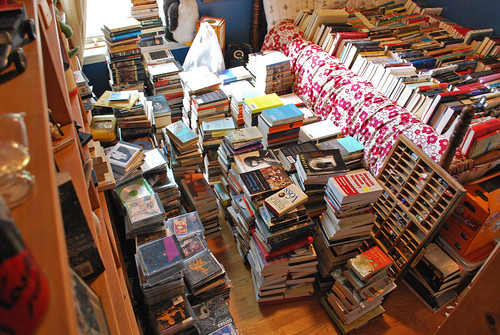

Desert Library Books?

{Photo by rocketlass.}

Being not much of a joiner, I generally fail to participate in online memes and list-making, but one that was passed on by Terry Teachout and CAAF of About Last Night earlier this week was impossible to resist:

Rules: Don't take too long to think about it. Fifteen books you've read that will always stick with you. First fifteen you can recall in no more than fifteen minutes.Below is the list I came up with; I've added a link to those about which I've written before on this blog.

Anthony Powell/A Dance to the Music of Time

Jorge Luis Borges/Labyrinths

Italo Calvino/Invisible Cities

Haruki Murakami/Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World

Wendell Berry/A Place on Earth

Homer/The Odyssey

Herman Melville/Moby-Dick

Roberto Bolaño/The Savage Detectives

James Gould Cozzens/Guard of Honor

Leo Tolstoy/Anna Karenina

James Boswell/Life of Johnson

Thomas Hardy/Tess of the D'Urbervilles

Raymond Chandler/The Long Goodbye

Marcel Proust/In Search of Lost Time

Sarah Orne Jewett/The Country of the Pointed Firs

Some that nearly made the cut, and on a different day might have done so:

Iris Murdoch/The Nice and the Good

Evelyn Waugh/A Handful of Dust

P. G. Wodehouse/Summer Lightning

Charles Dickens/Our Mutual Friend

Rebecca West/The Fountain Overflows

Claire Tomalin/Samuel Pepys: The Unequalled Self

John Crowley/Aegypt

F. Scott Fitzgerald/The Great Gatsby

Juan Rulfo/Pedro Paramo

I don't know that my list, even in its expanded version, tells you much about me; perhaps merely that my taste, though definitely biased towards the English, is fairly catholic, varying wildly depending on mood and circumstance.

Do take a look at CAAF's list (with which I have no titles in common) and Terry's list (with which I share three), both of which feature books worth recalling. Other lists worth checking out that I've come across so far are those of Patrick Kurp of Anecdotal Evidence (who eschews the term "meme," choosing instead the more pleasant and apt "literary parlor game"), who shares my fondness for Boswell and reminds me that Joseph Mitchell really ought to have found a place, and D. G. Myers, with whose list mine overlaps not a whit--though the titles I've read on his list are nonetheless favorites, which makes me think I ought to investigate the rest as well.

And yours, dear reader?

Labels:

CAAF,

D. G. Myers,

Patrick Kurp,

Terry Teachout

Monday, January 28, 2008

Why I find myself dancing to those same old steps again and again and again

Because I proselytize so relentlessly on behalf of Anthony Powell and A Dance to the Music of Time, I'm always searching for relatively succinct ways in which to explain their virtues. I usually place the novels' attraction in Powell's--and by extension, his narrator Nick Jenkins's--insatiable curiosity about the myriad ways that people choose to live their lives; in the fourth novel, At Lady Molly's (1957), in explaining his decision to attend a country weekend that seems likely to be disastrous, Nick Jenkins accords curiosity its proper, exalted place:

Curiosity, which makes the world go round, brought me in the end to accept Quiggin's invitation.What raises Powell's curiosity in Dance to the level of art is that he leavens it with a real openness to difference, from ordinary English eccentricity to unexpected sexual predilections to inexplicable fixed ideas. That mix of curiosity and sympathy allows Powell to find nearly any person of at least some interest; his much-quoted response to charges of snobbery--that if there were a Burke's of Bank Clerks, he'd buy that, too--rings true for any close reader of Dance.

In the third novel,The Acceptance World (1955), Jenkins neatly sums up Powell's approach and highlights the way that it opens up our understanding of our own selves as well:

I reflected, not for the first time, how mistaken it is to suppose there exists some "ordinary" world into which it is possible at will to wander. All human beings, driven as they are at different speeds by the same Furies, are at close range equally extraordinary.In a 1951 review of the first volume, A Question of Upbringing, Julian MacLaren-Ross (who would later form the basis of one of Powell's most memorable characters) sets a similar assessment of Powell's technique in a broader context:

Mr Powell is, mercifully, a writer without a "message," either philosophical, religious, or political; he is content to examine without comment, and to illustrate through character in action, the changes in human nature brought about by the changing face of the social order in which we live; in other words, he is attempting to fulfill the novelist's only true vocation.To reveal those changes in character, Powell doesn't rely primarily on particularly dramatic events (though there are some, especially in the war novels); instead, as Terry Teachout puts it,

[T]hings happen--life happens--to Powell's characters, and as we watch them grapple with each successive occurrence, we realize that his interest is not in what they do but in what they want.And, as Powell demonstrates, what people want so often becomes who they are. If curiosity drives the world, desire--specifically the desire for power--is what risks ruining it. To say that Powell approaches all characters with sympathy doesn't mean that he refuses judgment; though he lets events and actions speak for themselves, we see multiple times the grievous consequences of betrayal, cruelty, and the self-interest that is determined to carry all before it.

Serving as a bulwark against these, concomitant with simple human kindness, is the creative act. As Jenkins reflects in the second volume, A Buyer's Market (1952),

[T]he arts themselves, so it appeared to me as I considered the matter, by their ultimately sensual essence, are, in the long run, inimical to those who pursue power for its own sake. Conversely, the artist who traffics in power does so, if not necessarily disastrously, at least at considerable risk.The arts may not be able to defeat the Widmerpools of the world, but they can at least create and sustain a rival way of understanding that world, one that the power-hungry will never begin to comprehend. Tariq Ali, at the inaugural Anthony Powell lecture at the Wallace Collection, located the creative act at the center of the novels:

What, then, is the central theme of the series? Creativity--the act of production. Of literature, of books, of paintings, of music; that is what most of the central characters are engaged in for the whole of their lives. Moreland composes, Barnby paints, X Trapnel writes, Quiggin, Members and Maclintick criticise and the narrator publishes books and then becomes a writer. What excites the novelist is music and painting, literature and criticism. It's this creativity, together with the comedy of everyday life, that sustains the Dance.Curiosity, sympathy, creativity: three strong pillars on which to rest a novel. Add a baroque, yet balanced, prose style and a fierce eye for comedy, and you've got the music for my very favorite Dance.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)