Nowadays, to the extent that Powell's Hollywood period is known at all, it's for his brief meeting with F. Scott Fitzgerald. (Side note to those possessing a time machine: some of us would really appreciate a bit more detail about the time he met Douglas Fairbanks. Was Fairbanks wearing a shirt? Were his arms akimbo? Did he laugh with insouciance? (No, yes, no, I presume.)) Powell goes into it a bit in his memoir, To Keep the Ball Rolling, an account that includes a brilliant aside that I've quoted before:

One could not fail to notice the tone in which people in Hollywood spoke of Fitzgerald. It was as if Lazarus, just risen from the dead, were to be looked on as of some doubtful promise as a screenwriter.What I didn't realize until recently was that Powell had written about the encounter, and his Hollywood time in general, at much greater length. The piece, originally published in the Times Saturday Review on October 3, 1970, was included in the Hemingway-Fitzgerald Annual for 1971, and it's well worth seeking out if you have access to a good library.

Powell's account of his own experience is as droll as you'd expect:

Of efforts to become a Hollywood script writer there is little more to say than that they were unsuccessful. My American agent had died during our weeks on the high seas. The replacement was antipathetic. This was getting off to a bad start.The meetings that followed, Powell, says, were "pursuing the mirage":

One became familiar not so much with the bum's rush, to use an old fashioned expression,as that stagnation of movement, total inanition where any action is concerned, to some extent characteristic of all theatrical administration, more especially when the art of the film is in question."To some extent characteristic" feels like the most fundamental Powellian phrase: he's categorizing, which is one of his essential modes, but at the same time he's leaving a gap--individuality, even as one necessarily sorts by type, is what matters.

What follows is a brief account of the accommodations, the lifestyle (as glimpsed by a more or less determined outsider), and the people--and then he gets to Fitzgerald:

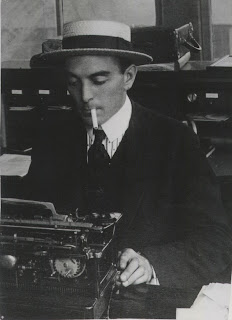

He was smallish, neat, solidly built, wearing a light grey suit and lightish tie, all his tones essentially light. Photographs--seen for the most part years later--do not do justice to him. Possibly he was a person who at once became self-conscious when before a camera. Even snapshots tend to give him an air of swagger, a kind of cockiness, he did not at all possess. On the contrary, one was immediately aware of a sort of unassuming dignity. There was no hint at all of the cantankerousness that undoubtedly lay beneath the surface. His air could be thought a trifle sad, but not in the least broken down, as he has sometimes been described at this period. In a railway carriage or bar, one would have wondered who this man could be.Powell and Fitzgerald seem to have hit it off, apparently monopolizing the conversation to such an extent that Fitzgerald eventually realized that neither Violet Powell, or their other luncheon companion, Elliott Morgan, had gotten a word in, a situation he good-naturedly tried to remedy.

What's of particular interest is Fitzgerald's assessment, at that moment, of his legacy. He was at low ebb, and knew it:

We talked of his own books. He dismissed any idea that they would ever be read in England. It certainly seemed unlikely then--a good example of the vicissitudes of authorship--that within 10 years and a world war everything Fitzgerald had written would be in print in a London edition.In the Paris Review interview, Powell credits Cyril Connolly, who was for a time all but the sole champion of Fitzgerald in the UK, for insuring that he knew of--and admired--Fitzgerald's work.

In the original article, Powell notes something that he only alluded to in the his memoirs: this was a moment--in fact, the very day--when a lot was happening in Fitzgerald's life. That evening, he would have dinner, for the first time, with Sheilah Graham, the woman who would be his companion in the final years of his life. Despite the emotional upheaval that surely accompanied the success of that dinner, Fitzgerald followed through with a note of thanks to the Powells for a pleasant lunch, and the gift of some books.

Even late, rackety Fitzgerald could regularly come through with some class.