That's V. S. Pritchett, writing about James Boswell. It's an aspect of Boswell's character I too often forget. I smile in appreciative amusement when I think of how he hoped his Corsican "adventure" would lead to his being known as Corsican Boswell, or at his combination of self-reproach, self-regard, and grasping ambition. (Pritchett catches that middle quality in a line plucked from the journal: "I think there is a blossom about me of something more distinguished than the generality of mankind.") But I too rarely think of Boswell the young man loosed on London, late of an uncongenial home, trying to make his way on little more than a family name and letters of introduction. We've been there, most of us, in some sense: just out of university, say, and attempting to build the foundations of our adult life. It can be lonely, tentative, frustrating. Pritchett depicts Boswell as "knocked off his balance by a severe Presbyterian upbringing," his will destroyed by his unappreciative father, to be

replaced by a shiftless melancholy, an abeyance of spirits.No wonder, then, that when Boswell did meet Johnson, he glommed on to him. Pritchett, rightly, credits Johnson--whom he goes so far as to call "saintly"--with "the steadying of Boswell's fluctuating spirit and . . . the sustaining of his sympathetic fancy." Boswell can frequently be ridiculous; he's never wholly unsympathetic, and never more so than when we view him through that lens.

From Pritchett I wandered to Cyril Connolly, a review of a volume of Boswell's journals on its publication in the 1950s. The first volume of the journals had, at that point, only been widely available to the public for about ten years, the reassessment of Boswell precipitated by its keen observations and self-awareness barely underway. "There has been a tendency to patronise him," wrote Connolly, "or find him a bit of a bore." Connolly, though acknowledging that the journals covering Boswell's time abroad aren't of the best, wasn't having it:

In the life of Johnson, Boswell subordinates himself to his hero who epitomised the age he lived in. In the journal, he allowed his own forward-looking sensibility full scope.And while Johnson, a figure who can make a reader's heart ache in sympathy with his internal and external struggles, can also be irritatingly self-important, Boswell is accessible. "It was his friend Johnson," writes Connolly, "who struggled so hard with the tragic sense of life. Boswell could always get drunk."

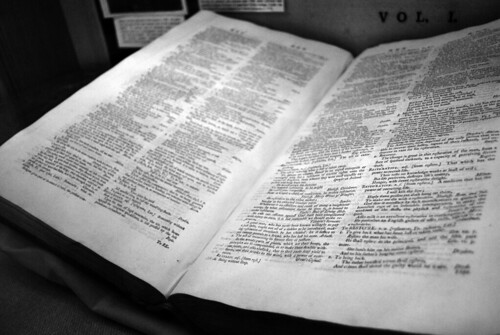

All of which led me back to the Journal, which is in its own way as inexhaustible as the Life of Johnson. Flipping through it, I hit upon an entry that followed a successful dinner party—success, for Boswell, meaning that the guest list was of a reasonably high standard, the conversation sparkled (and included him), and he didn't wake with a hangover. Reflecting on the evening, Boswell wrote, "I felt a completion of happiness. I just sat and hugged myself in my own mind."

Is there a better example of Pritchett's characterization of the Journal's genius, "the accidental and unforeseeable quality of life" it has, "which better organised, more sapient or more eloquent natures lose the moment they put pen to paper"? That simple expression--"hugged myself in my own mind"--is not one I'll forget; those two lines, now, will be how I, too, think of a good evening with friends.

.JPG)