{Photos by rocketlass.}

Sorry, can't blog today. Too busy reading Gillian Flynn's Dark Places.

Oh, fine. How about a quick crime novel roundup, and then I'll go back to trying to figure out what wonderfully horrible twist Flynn's going to surprise me with next?

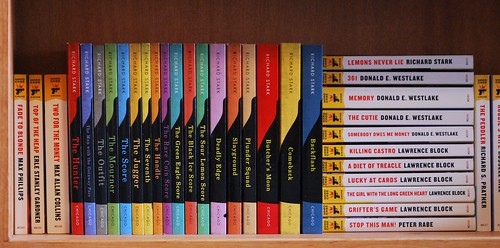

1 The new batch of Parker novels is out now from the University of Chicago Press: Flashfire (2000) and Firebreak (2001). They've got an introduction by Terry Teachout that's one of the best we've published. Teachout points out that despite his sociopathic tendencies, "Parker kills only when absolutely necessary, a clear sign that he isn't crazy"; does a nice job of drawing the distinction between Stark's Parker and Westlake's Dortmunder; and quotes my favorite Dortmunder line, which just might be my favorite Westlake line, period:

Whenever things sound easy, it turns out there's one part you didn't hear.Flashfire is one of the best in the series, featuring a lot of heists, a strong female character (who's a civilian, no less!), and some truly great exchanges between Parker and a Florida sheriff. It's easy to why Hollywood chose this one to launch the upcoming Parker movie series.

2 Over the weekend I continued my progress through the rest of Westlake's novels. I started with a darkly comic novel called Two Much (1975), in which one of Westlake's least honorable and least likable protagonists cons two rich twin sisters into thinking that he, too, is a twin--and a separate twin is sleeping with each sister. It's a great example of two Westlake strengths: his enjoyment of playing out the implications of a puzzle he sets for himself and his understanding, most clearly on display in the Parker novels, that our instinct as readers is to want the narrator to get away with what he's doing almost regardless of how awful it is or how amoral he is. Present us with a problem and we want to see it solved; Westlake knew that better than anyone I can think of.

3 The other Westlake I read this weekend was refreshingly light: Good Behavior (1985), which finds John Dortmunder and his gang trying to kidnap a nun . . . on behalf of her convent. It won't surprise you that the gang ends up dressed in habits:

Very strange. When nothing shows but your face, enclosed by the white oval of a wimple and the featureless black of a nun's costume, you wouldn't expect much by way of individual character to show through, but it did, it did. . . . Tiny, whose face mostly consisted of knuckles anyway, was barely plausible as the kind of false nun who, in the Middle Ages, poisoned and robbed unwary travelers. Stan Murch looked like a pilgrim in The Canterbury Tales, probably the one with ideas for alternate routes to Canterbury. . . . Kelp was surely someone whose sister was the pretty one, while Dortmunder looked mostly like a missionary nun who was already among the cannibals and headhunters before realizing she'd lost her faith.It's all as ridiculous as it sounds, and it makes for one of the best of the Dortmunder series.

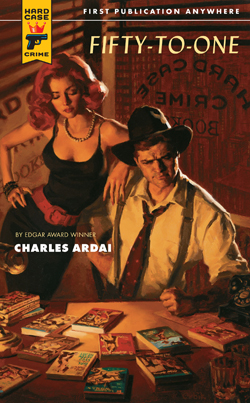

4 While Hard Case Crime will officially mark their welcome return next month with the publication of Lawrence Block's new book of smut and crime, Getting Off (which I'm looking forward to reading soon alongside Nicholson Baker's new book of smut and smut, House of Holes), they'll also be publishing a new book by Max Allan Collins, Quarry's Ex (2011). Collins is at his best when writing about Quarry, whose character is perfectly suited for Collins's tight mix of violence, quips, and social observation, and I've really enjoyed watching him flesh out the hitman's backstory these past couple of years. Quarry's Ex is a strong addition to that story. It should show up in stores in September; it's available for pre-order now.

5 I'll close by returning to Gillian Flynn, so that I can return to reading Gillian Flynn: last summer, at the start of the annual Stahl family vacation, I gave a copy of Flynn's first novel, Sharp Objects, to my sister. She blazed through it, then lent it to my brother. As he was nearing the end, my sister and I sat and watched him, waiting for him to get to that part, so we could see how he reacted. He kept looking up and laughing at us . . . and then he got to that part. He stopped laughing.