{Photo of our detective nephew by rocketlass.}

1 From Deadly Beloved (2008), by Max Allan Collins

"'Examine the past, understand it, then leave it behind . . . and move on.' Great advice, Doctor. But as a detective I spend at least as much time in the past as in the present."Are there any fictional detectives to whom that doesn't apply? Off the top of my head, I can think of a couple, such as Matthew Scudder or Derek Strange, who seem to traffic a bit more in crimes of the moment, but they seem more than balanced by those, such as Lew Archer, who are forever dealing with the lingering consequences of people's past, secret mistakes. Any strong exceptions worth noting?

"The nature of your business."

2 Monday on "Fresh Air" Terry Gross interviewed Charles Ardai, the founder of Hard Case Crime. We all know that Gross is a good interviewer, and Ardai turns out to be a comfortable and interesting interview subject. It was fun to learn that he became a noir fan through high-school readings of Lawrence Block, whose Grifter's Game (1961) was the first book published by Hard Case. The most surprising thing I learned, however, was that the reason the retro-style cover paintings that grace Hard Case's books are a tad less salacious than those of the pulp era is not because of decorum on the part of Ardai and cofounder Max Phillips, but because of prudery on the part of major retailers such as Wal-Mart. The big chains say no nudity, so the painters opt for artful draping and incomprehensibly complicated lingerie instead.

Gross also talked to Ardai at length about the two novels he's written under the pen name Richard Aleas, Little Girl Lost (2004) and Songs of Innocence (2007). I've read all but a handful of Hard Case's titles, and Songs of Innocence just might be the best of the lot, challenged only by a couple of the Block novels. Carrying us along as his young, damaged detective quickly gets in over his head, Aleas brutally gives the lie to the more wish-fulfilling aspects of crime fiction--and thus opens up the true, dark heart of noir. It's been nearly a year since I read the book, and it has only grown in my estimation since.

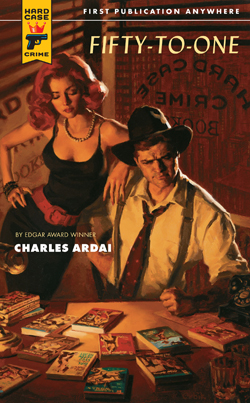

3 Ardai is currently writing Hard Case's fiftieth book, Fifty-to-One, to be published under his own name at the end of the year. Unexpectedly, it's a comedy, written in fifty chapters, each named after a Hard Case Crime novel. That qualifies as Oulipean, if just barely . . . but--question for Ed--might it also count as an Ouroboros? Especially once you see that the cover features tiny versions of a bunch of the Hard Case covers?

4 Speaking of cover designs, Rex Parker's Pop Sensation blog recently highlighted this unforgettable cover from a 1965 Pocket Books edition of Raymond Chandler's The High Window:

In the post, Parker points out that the man does look a tad goofy if you look at him too closely:

If you turn the book upside-down, that guy looks like your dad pretending to be a monster after he's had a hard day at work / a little too much to drink.But I still call it a successful cover. After all, if you were at the train station waiting anxiously for the 3:22 AM to Utica, hat pulled down and collar turned up to hide your face, trying to look all casual by lazily turning the paperback spinner . . . wouldn't you stop cold on that one?

5 Though my blogger profile mentions that I work in publishing in Chicago, and .22 seconds on Google will dig up the name of my employer, I've never mentioned their name directly on this blog, both because it never seemed necessary and because, as my friend Luke puts it, "Getting fired for your blog is so 2002."

But excitement about some forthcoming books has convinced me to break my silence: I work as the publicity manager for the University of Chicago Press, and this summer the Press will be publishing the first three of Richard Stark's Parker novels. The Press's first venture into the hard-boiled underworld began when I dropped copies of The Man with the Getaway Face (1963) and The Outfit (1963) on the desk of my colleague who acquires out-of-house paperbacks, along with an explanation (including this post) of why I thought we ought to reprint them. Within a couple of days, she was hooked, too, and the Press--which had previously published some mysteries, including Robert Van Gulik's Judge Dee mysteries and Friedrich Durrenmatt's deconstructionist Euro-noirs--had picked up rights to those two, as well as Stark's first Parker novel, The Hunter (1962).

Not only did this mean that we got to commission great new cover illustrations, which I'll share when they're available, but it also meant that I got to write some serious crime copy:

You probably haven’t ever noticed them. But they’ve noticed you. They notice everything. That’s their job. Sitting quietly in a nondescript car outside a bank making note of the tellers’ work habits, the positions of the security guards. Lagging a few car lengths behind the Brinks truck on its daily rounds. Surreptitiously jiggling the handle of an unmarked service door at the racetrack.Though I'd read some Westlake and some Stark before, I read my first Parker novel on the way to visit my family at Thanksgiving. I've read fourteen more in the six months since, and I'm not the slightest bit tired of them. I imagine that the feeling of being involved with these reprints is similar to what Charles Ardai felt when he signed up his first Lawrence Block--and now I'm looking forward to years of aiding and abetting Parker's criminal ways.

They’re thieves. Heisters, to be precise. They’re pros, and Parker is far and away the best of them. If you’re planning a job, you want him in. Tough, smart, hardworking, and relentlessly focused on his trade, he is the heister’s heister, the robber’s robber, the heavy’s heavy. You don’t want to cross him, and you don’t want to get in his way, because he’ll stop at nothing to get what he’s after.

6 All of which means that I really ought to expand on the disclaimer that I vaguely offer in my blogger profile, just to be clear, before I return to my usual approach of not mentioning work. How's this?

This blog is entirely separate from my job, written only in my non-work hours. The opinions are mine alone and are offered neither at the behest of or with any restraints from my employer. If you want to believe that my manifest enthusiasm for my favorite novel, Anthony Powell's A Dance to the Music of Time, published by Chicago, could possibly be feigned, then I'll take your name and call you the next time the Continental Op needs the services of a professional cynic.