{Photos by rocketlass.}

In a review of two new biographies of Samuel Johnson (including Peter Martin's, about which I've written a bit before) in this week's New York Times Book Review, Leah Price succinctly notes one of the reasons that Johnson these days is more heard of than read:

We tend to go to past authors looking for kinds of writing that remain familiar today: single-authored, volume-length, recognizably literary works, especially novels.Aside from Rasselas, which can be tough sledding for someone not already attuned to Johnson's thought and times, Johnson wrote no novels, nor did he write anything of convenient book length, the sort of work that one can chuck in one's bag and read on the subway for a week, from start to finish. Rather, as Price explains,

His best work was topical, collaborative, and either journalistic (especially the twice-weekly essay-periodicals like The Rambler, which he turned out as regularly as any blogger) or editorial (whether in the form of compilations, abridgments, translations or even a library catalog).That said, the obstacles to reading Johnson today really aren't that great, once one realizes that he is best encountered in his essays: Oxford World's Classics publishes a bulky and satisfying volume, The Major Works, that provides a more than satisfactory introduction to Johnson, offering the best of his essays for the Rambler and Idler, a selection of his poetry, a few of his Lives of the Poets, and a generous selection of his incidental prose. It's a volume to leave on the nightstand or keep perpetually in one's shoulder bag, to be read a few pages at a time over the course of years.

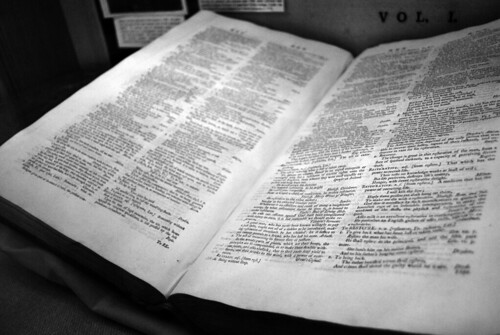

That method doesn't really work, however, for Johnson's most astonishing achievement, his Dictionary. It's hard to find in unabridged form and unbearably awkward if so found--and even then, its form doesn't lend itself to the sort of constant, slow perusal appropriate to his other works. After all, dictionaries aren't exactly books for reading; even the best of them tend to pall once one's read a few pages straight through. Despite the Dictionary's many fascinating idiosyncracies, it's hard to imagine anyone without a professional interest in Johnson actually reading the whole volume cover to cover.

Fortunately, Yale University's Beinecke Library (the same people who bring you the wonderful Room 26 Cabinet of Curiosities blog) has come to the rescue: to celebrate Johnson's tercentenary, the Beinecke has started a blog on which they will post a new word from the first edition of the Dictionary every day. We're less than a month into the year--they've just crossed into "C"--and the project has already offered numerous delightful definitions.

Probably my favorite thus far is By-Coffeehouse--

BY-COFFEEHOUSE. n.s. A coffeehouse in an obscure place.--which makes me want to adopt the term By-Bar, for a second-floor or alley bar; your help in the word's promulgation will be appreciated.

I afterwards entered a by-coffeehouse, that stood at the upper

end of a narrow lane, where I met with a nonjuror.

Addison. Spectator, No 403.

I'm also very partial to Browbeat, which Johnson defines thus:

To BRO’WBEAT. v.a. [from brow and beat.] To depress withToday, Merriam-Webster's defines browbeat a bit more metaporically--

severe brows, and stern or lofty looks.

It is not for a magistrate to frown upon, and browbeat those

who are hearty and exact in their ministry; and, with a grave,

insignificant nod, to call a resolved zeal, want of prudence.

South.

What man will voluntarily expose himself to the imperious

browbeatings and scorns of great men? L’Estrange.

Count Tariff endeavoured to browbeat the plaintiff, while he

was speaking; but though he was not so imprudent as the

count, he was every whit as sturdy. Addison.

I will not be browbeaten by the supercilious looks of my ad-

versaries, who now stand cheek by jowl by your worship.

Arbuthnot and Pope’s Mart. Scriblerus.

To intimidate or disconcert by a stern manner or arrogant speech : bully--which definition it does seem that the good Doctor, who was not known for the subtlety or tolerance of his disputation, might have grudgingly appreciated.

There's so much more worth perusing, from defunct words that could bear resurrection--such as "breakpromise"--to words whose definitions run off the rails, as in the case of "bezoar.". Put this one in your RSS reader, folks--you won't regret it.

{The Beinecke will also be mounting an exhibition this summer on the writing of Boswell's Life of Johnson, which means I really need to find a way to make it to New Haven the next time I'm in New York.}