Which is one reason that I always notice when Archie mentions that Wolfe once in a while watches TV. Wolfe gets a TV pretty early--a real Stout fanatic would have the date at his fingertips, but I'll just say I vaguely remember him having one in a novel from the very early 1950s (and having a remote for it!). But Death of a Doxy (1966) is the first time I've encountered any specifics about what Wolfe actually watches. Archie, having been out all day on a Sunday, thinks it likely that while he was gone Wolfe engaged in

his weekly battle with television. That may occur almost any evening, when he has got disgusted with a book, but usually it's a Sunday afternoon, because that's when TV is supposed to be dressed for company. He turns on one channel after another, getting grimmer and grimmer, until he's completely assured that it is getting worse instead of better, and quits.What Wolfe fan doesn't immediately want to know what Wolfe was watching on that Sunday in January or February of 1966?

I turned to my old friend Jim Ellwanger, whose knowledge of TV is encyclopedic. Within hours, he'd replied in great, fascinating (to this fan of Wolfe and TV history) detail:

My first thought is that my father turned 17 in February 1966, and being in New Jersey, he got the same TV channels Nero Wolfe did in Manhattan -- and probably had the same opinion about them.As they say: education isn't so much about knowing the answer to a question, as knowing where to get the answer. Jim, that's where.

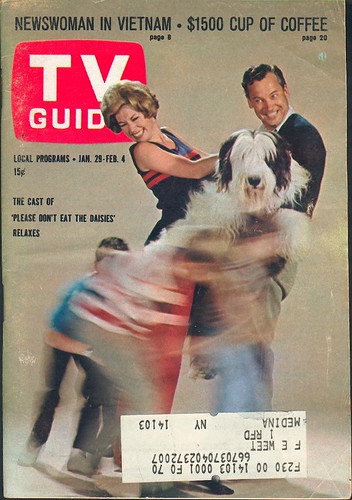

Anyway, I actually have a TV Guide from the time period in question, the January 29, 1966, issue.

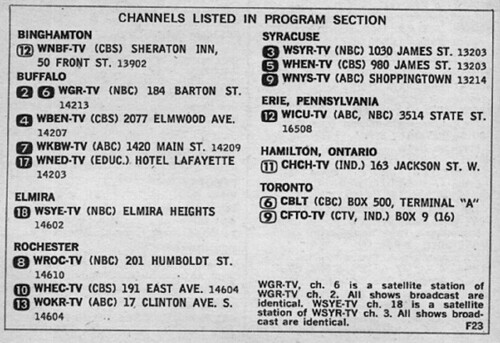

It's not the New York City edition, it's the Western New York State edition. Still, I can tell you exactly what network shows aired (and it's a pretty safe bet that they all aired on the owned-and-operated stations in New York):

12:30 (CBS) Face the Nation: "Scheduled: Secretary of the Treasury Henry H. Fowler is interviewed in Washington by CBS News correspondents Martin Agronsky and David Schoumacher; and Edwin L. Dale, Washington Bureau, New York Times. (Live)"

1:00 (NBC) Meet the Press: "(COLOR)" [unfortunately, no further details in this TV Guide]

1:30 (ABC) Issues and Answers: "Former Vice President Richard M. Nixon is interviewed in New York City by White House correspondent William H. Lawrence." [This is the predecessor to what's now "This Week."]

2:00 (ABC) NBA Basketball: "The Cincinnati Royals meet the Hawks at Kiel Auditorium, St. Louis. Chris Schenkel and Bob Cousy report. (Live)"

2:30 (CBS) CBS Sports Spectacular: "Scheduled: hunting and bowling. The finals of the $100,000 National Individual Match Game Bowling Championships are telecast live from Lansing, Mich. Also: Hunting authority Lee Wulff narrates films of turkey and quail shooting in Georgia. (Live and tape; 90 min.)"

4:00 (NBC) NBC Sports in Action: "Scheduled: lumberjacking and the Wengen International Ski Races. The ski races started Jan. 11 near Wengen, Switzerland. The World Lumberjack Championships were held last fall at Hayward, Wis. (60 min.)"

4:00 (ABC) The American Sportsman: "(COLOR) Actor Fess Parker joins guide Fred Bear to track down a Canadian grizzly in Northwestern British Columbia. Off Islamorada, Fla., fishing expert Joe Brooks goes after tarpon. Also: a comic underwater look at an Australian grouper (sea bass) that can't decide whether to swallow an attractive but somewhat suspicious piece of bait. (60 min.)"

4:30 (CBS) Ages of Man: "(SPECIAL) Sir John Gielgud reads from the works of Shakespeare in the conclusion of this adaptation of his one-man Broadway show. (60 min.) 'Mister Ed' is pre-empted." [In this, its final season, the regular time slot for "Mister Ed" was Sundays at 5:00 -- its last first-run episode aired 2/6/66.]

5:00 (NBC) Mutual of Omaha's Wild Kingdom: "(COLOR) 'Chacma Country,' second of a two-part study of the chacma baboon. In Southern Africa's Victoria Falls region, host Marlin Perkins and Jim Fowler follow the baboons on a search for water and food."

5:30 (NBC) G.E. College Bowl: "(COLOR) The University of Tulsa (Okla.) vs. Newcomb College, New Orleans. Moderator: Robert Earle. (Live)"

5:30 (CBS) Ted Mack's Original Amateur Hour: "Ted Mack introduces tenor Victor LaTorre; the Dukes, vocal-instrumental group; Elyse's Twirlettes, baton twirlers; singer Ronald Henry; tap dancer LaVerne Huselton; the Fraine Brothers, vocal group; ventriloquist Cassie Booker; and singer Linda Powell."

In addition to Nero Wolfe's network stations (2/WCBS, 4/WNBC, and 7/WABC), he also had three independent stations (5/WNEW, 9/WOR, and 11/WPIX) and an educational station (13/WNDT), and, if he could get UHF, he also had a second educational/public-interest station (31/WNYC). The latter two may not have been on the air for all of Sunday afternoon; the one educational station in Western New York, 17/WNED in Buffalo, didn't sign on until 4:00 P.M., and its programming looked like this:

4:00 Antiques: "George Michael shows a collection of antique bottles, and describes their origins and uses."

4:30 French Chef: "Julia Child shows how to prepare Reine de Saba (Queen of Sheba) cake."

5:00 Open Mind: "'What Kind of Preschool Education for Your Child?' A discussion of the relative merits of the progressive, public and Montessori methods of early education. (60 min.)"

As for the programming that aired on the independent stations, as well as on the network stations in between network programming, there were a couple of syndicated series and specials that were on multiple stations in Western New York:

The Flying Fisherman: "(COLOR) Gadabout fishes for bass at Reelfoot Lake in Tennessee."

Ski Championships: "(SPECIAL) In the first of three televised meets sponsored by the newly formed National Professional Ski League, skiers compete individually and as members of three-man teams. Entrants in today's races, taped Jan. 26-27 at Stratton, Vt., are Olympic gold medalists Stein Eriksen (Norway), Pepi Gramshammer (Austria), Christian Pravda (Switzerland), and Hias Leitner (Germany). (60 min.)"

Other than that were the movies. Some of the titles that aired in Western New York on this particular Sunday:

The Ghost Goes West (1936)

Elephant Boy (1937)

Ma and Pa Kettle (1949)

The Son of Hercules in the Land of Darkness (1964)

Reap the Wild Wind (1942)

Drum Beat (1954)

Damn Yankees (1958)