{Photos by rocketlass.}

The headline of this post comes from an admonition that Samuel Johnson reportedly received from an old man at Oxford in 1763 who urged him, "Ply your book diligently now," before old age robbed him of his thirst for knowledge. Johnson, forever afraid of his natural indolence, took the urging to heart, making up a plan; here's how Peter Martin explains it in his thoughtful and well-written new Samuel Johnson: A Biography (2008):

On 21 November 1729, in an effort to get down to study, he made a self-disciplining table of how much reading he could get done in a week, month and year if he read ten pages per day: 60, 240, and 2880 respectively. To begin with a meagre ten pages per day may suggest just how indolent he thought he had become. He soon realized that ten pages per day would get him nowhere, so he tabulated what he could achieve based on 30, 50, 60, 150, 300, 400 and 600 per day, though he did not take the last four as far as computing annual totals, realising the stark fantasy in such an exercise. Sixty would yield 17,280 for a year, and apparently he thought that was as much as he could realistically read. Such computations would become almost chronic with him as he struggled to impose order on a sense of disorder, "as it fixed his attention steadily upon something without, and prevented his mind from preying upon itself." He even counted the number of lines to be read in The Aeneid and other works by Virgil, as well as in works by Euripides, Horace, Ovid, Theocritus and Juvenal.I remember making calculations of that sort when I was a teenage boy who loved math and ordered systems; the tendency reappears now and then in my adult life, usually when I'm contemplating a seemingly insurmountable stack of pages requiring careful proofreading. For the most part, though, I'm satisfied these days with making some progress on one or two of the several books I'm always lugging with me on my commute, numbers and plans be damned.

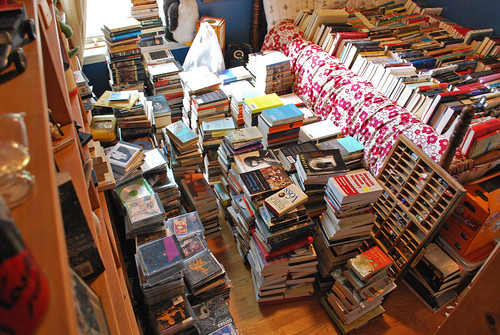

Given my recent preoccupation with the copious quantities of unread matter lining the walls (and, let's be frank piled on the floor) of my house, it probably won't surprise you that I was struck by Johnson's approach to the problem. More troubling, however, for the bibliophile surrounded by books, is this account later in the biography of the fate of Edward Harley, the cataloging of whose vast library Johnson took on as paid work in his pre-Rambler, pre-Dictionary years:

Harley, friend of Pope and son of Robert Harley the Tory Lord Treasurer in the reign of Queen Anne, was owner of the great estate of Wimpole Hall in Cambridgeshire. He owned a vast collection of books, manuscripts, and tracts that he housed at Wimpole Hall, his house in Dover Street, and his magnificent mansion in Cavendish Square. The size of the collection included some fifty thousand books and seven thousand volumes of manuscripts, not to mention coins, engravings, Greek and Roman antiquities, and more than five hundred paintings.That doesn't sound bad, does it? So what's the problem, you ask? Why does this book blogger, who mere months ago broke down and bought all-new bookcases, feel a chill wind sweep over him on reading about Harley? Because Martin goes on to explain:

His need to build elegant places to house them eventually brought on severe financial worries that may have hastened his death.If you need me, I'll be over here, culling my shelves for donations to the Chicago Public Library.